How To Create Animation

How To Create AnimationInterviews by John Cawley Storyboards PETE ALVARADO INTERVIEW DATE: AUGUST 27, 1990 Back To Contents Back To Main Page |

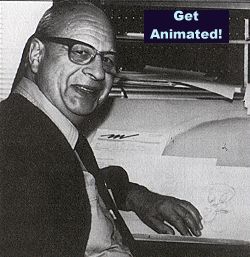

INTRODUCING PETE ALVARADO...

Pete Alvarado has been working in animation since the classic era of the late Thirties. By the Forties he was at Warners working on the Jones unit doing a variety of chores. He's done animation, layouts and background paintings. (His backgrounds graced the first Road Runner cartoon.) In the Fifties he began doing comic books and kept busy for years. When TV animation came along he was there doing not only layouts, but now storyboards. Today he still keeps busy for numerous studios providing storyboards, advice and a cheery spirit.

We caught up with Pete at his home via the phone. The current boom in animation has put even more demand on his considerable talents, and there didn't seem to be enough hours in the day for a sit-down meeting. However even on the phone, Pete's love and enthusiasm for the business was evident.

Q: Can you give me a brief description of your career including

studios you've worked for and specific productions you've worked

on?

PA: Well, let me see. I might as well start with Disney because

that goes back to 1937 and the tail end of SNOW WHITE. I didn't

stick around Disney's too long. I went on to Warner Brothers and

other places. I went back to Disney briefly for a few months

during DUMBO, but it didn't seem to click. Then, there was a

period where I went with MGM.

I was doing basic animation like inbetweening and the nuts and

bolts; learning the thing from the ground up. Everyone, at that

time, had to pay their dues and put in their apprenticeship.

Some places had what they called "the bullpen." Everyone would

do basically the same things, clean up and inbetween or whatever

was required, and it was pretty tedious stuff, and I was very

happy to get out of it (laughs). Most of the guys were.

Anyway, that was something that everyone seemed to have to do, at

that time before they branched out into the other specialties.

Fundamentally, I was doing animation although I was always

leaning toward wherever I could try to find out where they were

doing the story sketches or backgrounds or more creative stuff

like character design... that kind of thing.

My training in art school was fine arts. It being the Depression,

most of us in the art school were thinking about making a living

with our art. At that time, Disney was the big employer in town.

And so that's why most of the talent in the art school ended up

with Disney's, at least for a while.

My first tour at Warner's was the black and white Bob Clampett

unit, doing the Porky Pigs and stuff like that. This is before

World War Two, of course. I then moved to MGM and worked with

Hanna and Barbera. They allowed me to do some assistant layout

work with Harvey Eisenberg (Jerry Eisenberg's father). He was

doing the Tom and Jerry's at that time. Hanna and Barbera were

looking around for artists that could replace him because Harvey

was thinking of moving to the Barney Google comic strip. The

strip's artist, Billy De Beck, was ill and the syndicate was

looking for artists. Harvey tried out, but he was eventually

turned down, although he was a superb artist. Actually, it was

very flattering to be thought of as a replacement for him.

Then I had a hiatus in the service for a couple of years, and

upon coming back, I decided I was going to try to really get into

the more creative end of the business. From that point, I really

slanted more toward layout, character design, that type of thing,

and background painting.

Then my second stint at Warner's began. It was interesting. I

happened to hit at a time when Chuck Jones was in a period where

he produced a lot of very, very good films. He had a lot of

talented people working for him at the time. I considered it

really a stroke of luck (laughs) to be with them. There were top

people like Tedd Pierce and Mike Maltese and Warren Foster;

animators like Ken Harris, Ben Washam, Abe Levitow. I really

enjoyed working with Chuck, and there were men like Bob Givens,

also. Well, I had known Bob before in the old days of black and

white, before World War Two, but we became reacquainted with the

Jones unit.

We created a lot of new characters and it was just a very

prolific period for everybody. I'd say it was one of those

unique situations where people would spin off of one another.

Because the talent around you is so good, you have to hit for a

higher level of quality, and I think that had a lot to do with

it. We did a lot of films and things like the Road Runner and

Pepe Le Pew and, oh, you could name a slew of them.

I then heard that Western Publishing was coming out to the [West]

coast. They were setting up an office out in Beverly Hills, and

looking for artists. They had Carl Barks, one of the first ones

they hired, and then, Jesse Marsh from Disney. With Western

Publishing, I ran into an interesting thing. They offered

contracts which, at the time, were unheard of in the animation

business. So I grabbed it. I began to divide my time between

the studios and Western, doing books. They not only did comic

books, but the Little Golden Books and all kinds of games and

puzzles and you name it. I did that until Western went out of

business (laughs). Well, they're still in business, more or less.

But I do it by mail now to the East Coast. I guess you can say I

was just about the last contract artist Western had until they

closed their L.A. office.

I was soon doing a lot of work for Hanna-Barbera, particularly

layout and character drawing, stuff like that, for THE JETSONS,

YOGI BEAR, and FLINTSTONES. I would wear two hats (laughs). I had

six months at the studios and six months of books. I did that

for a lot of years. I also did a lot of burning the night oil.

But it worked out pretty well because of the way the television

season worked. The studios would phase out around September or

October, and that was just about the time I'd start doing my

books.

I also worked at other studios. I worked for Bakshi-Krantz on the

daring FRITZ THE CAT, NINE LIVES OF FRITZ THE CAT. There were periods with DePatie-Freleng when they were doing different kinds

of shows like the Pink Panther and other things. I kind of

alternated between whoever was busiest. But I would basically

say Hanna-Barbera, for many years, was pretty much one of my base

studios that I did a lot of work for.

Q: When did you get into actual storyboarding?

PA: I guess I did some in the 50s. I really got into boarding

with television. I got my feet wet doing just spec stuff. I

began to board a little later on, after they'd run out of layout

work or something like that. Or maybe I'd start the boards and

then eventually work into the layout. When all the runaway

production stuff started, then I really seriously thought about

storyboarding to fill the gap. With all my training in layout and

other things, I figured that I should be able to handle boards.

Of course, comic books were good training, too, learning how to

stage stuff in a given area quickly and simply.

I always felt storyboarding was such a highly specialized type of

thing. The men I knew were men who worked on Disney features and

that kind of thing. I admired these guys. To be a good

animation story man, you have to have a special something, I

don't know what it is, besides being an artist or a writer. I

always felt frustrated. The ability to write and draw a

storyboard is more satisfying than just drawing it.

Q: What was your art training?

PA: I had a scholarship at Chouinard's at the time. They're no

longer in existence. I guess you could say CalArts was the

outgrowth of Chouinard. Mrs. Chouinard was a terrific woman,

[she] loved her students. During the period I was there, Disney

came in and assisted the school financially. It gave them an in

to her most talented students. It was a great way to find talent

when you think about it. And, of course, the students didn't

feel too badly because jobs were kind of scarce, and Disney's was

a good way to go.

Q: Is that basically how you broke in, by going that way?

PA: Yeah. Like I say, Chouinard taught an animation class, and a

lot, maybe 95% or more, of the students who went into the class

immediately went over to Disney's when they finished. So, it was

almost like a Disney training school. Then Disney, himself, had

classes going at his studio. So, we were constantly learning.

We were training on the job. It was kind of a good era, in a

way. Unlike a lot of the studios today, they actually considered

it very important. In order to have a pool of trained talent,

they would go to the expense of training them themselves if they

had to. So (laughs) that's unique. Disney paid people while they

learned. I don't know why one of the producers today doesn't

break out and do that. If you really want trained talent, train

them your way.

Q: What does a storyboard artist do?

PA: The way I approach it is you've got an animation script.

You've got a fundamental story line maybe with gags interspersed

or something like that. I think that I've always approached it

like an underlying story, and then try to put some acting into

the character. Make the characters act, make them breathe, if

you can. Like when you do layout and do characters, you try to

put a little life into the thing.

I think a lot of fellows just crank out panels. They don't mean

anything. And I think a lot of times, it's my belief anyway,

that if you put something into the board that has a lot of guts,

a good animator will pick up on it. I know this to be true

because of the fellows I've worked with. They've mentioned back

to me that they like the board I gave them because it kicked them

off on something. They had fun and stuff came out looking good,

better than it would have.

I'll never forget one time I was talking to Friz Freleng about

it. I said, "Gee, do you think we're wasting our time, making

nice looking drawings on the board?" He said, "Well, look at it

this way, in television, as it goes down the line, it loses. It

gets less and less. Everything you put in up front will mean

something." In other words, it'll be much better than it would

have been. It's a good philosophy, really.

I think, you should have a little fun or pride in what you do,

and maybe have a little fun with it. But, go at it with some

kind of pattern. Even if a lot of times you get a lousy script,

and you say, "Gee, this is terrible." The challenge is: what can

I do to make it better than it is, or better than it deserves

(laughs)? And sometimes, occasionally, you can come up with

something extremely funny. One little bit, out of a whole half

hour maybe, will be a belly laugh. People will remember it.

They'll say, "Gee, who did that funny thing?" It's just a few

seconds, but it's so well done, it comes like a shock (laughs).

It's the same with all other art work. Say an ad agency gives

you something, and it's a campaign that's dull. What can you do

to make it better than it is? Can you liven it up? What can you

do to get an audience to look at it? That's the whole thing.

How do you grab the audience? Or how do you make somebody stop

and look and listen. I don't think it's anything earth shaking.

I think we're entertaining. Maybe some day we'll get into

messages, I don't know (laughs). But, right now, I think we're

entertaining.

If you can inject a message painlessly, well, fine. That's good.

It doesn't hurt. But I think, to entertain, to try to take each

board you get and inject something into it that'll liven it up or

will grab the audience. There's a lot of things you can do, a

funny attitude or maybe the way you build up the personality of a

character.

Q: When do you usually get involved with a project?

PA: Well, as a rule, they call you and they say, "We've got this

series coming up and we've got X number of shows," or whatever. They usually have their outlines, but most of the time, (laughs)

I don't pay too much attention to them. I wait until after I do

a few of the scripts, then I get a feel for the characters and

the story line and the flavor that they want. I think a lot of

times, they do them so fast, that the men that create them don't

realize, the potential until they actually see it on the air.

Q: How much assistance do you get from the director or the

writer?

PA: Well, it depends on the director, the writer. I've found in

recent years some of the fellows can be kind of hardnosed. They

have certain ways of doing things, and certain directors wanted

to see certain things. Every time, you'd have to prove yourself,

or something. Then, other directors were very good about letting

you have your freedom. They would hope you'd come up with

something clever, unique, or different, or new, or something like

that. Each one seemed to be a little bit different from the

other. So, I would say they really aren't all the same, they're

just (laughs) human beings that react. Some men in the business

don't find anything funny (laughs). Then, I know there are other

men who will laugh at every gag no matter how bad it is (laughs).

Q: What is your daily routine like as a storyboard artist?

PA: Well, I used to be a nine to five guy, but I've somehow

gotten into a lot of night work where things are quiet, so I just

shift my hours. I do, basically, the same number of hours, or

maybe even a few more. But, I find that a lot of times at night,

without any phones ringing or other things to interrupt, I get a

lot more done. I can operate on a very small amount of sleep, so

I'm fortunate that way.

I would say I put in my eight hours or more, at least eight

hours, and I sit there, and even when something doesn't feel like

it's going to work, I just sit there and keep drawing until it

does. I don't wait to be inspired. But, occasionally, there are

times when I'll go back and maybe look at some of my fine art

books or other things, or get a good novel or a good piece of

literature or something... get a little change a pace and then

come back to my work refreshed.

Q: Do you use any reference or a lot of reference in your work?

PA: Yes, I have my own personal file of my reference. Over the

years, I've had a lot of material that I've used, and I

constantly refer back to that. I do surround myself with a lot

of reference. So, that probably gets injected into the work too.

Q: One thing you hear a lot is that storyboards are sort of like

comic books or comic strips. That's often a simplified way of

describing it. You've worked in both. Can you say that it is an

accurate description?

PA: Well, one art director at Western mentioned that I could adapt easily, but I found that I thought of the two things as

separate media. A comic strip is a separate thing from an

animation storyboard. I always think of an animation storyboard

drawing from the standpoint of layout or animation, that kind of

thing. I'm always thinking: what will the animator do with this?

What will the layout person do with this? Can they take this and

can they build on it, or something like that?

The comic strips and comic books, I recall mainly: How can I

eliminate characters (laughs) and make close-ups? Or how many

silhouettes can I get to a page (laughs)? I think a lot of us in

the business had a few laughs about that. They finally did

restrict us to one silhouette a page (laughs). Contrary to what

you see today in comic books, where they're usually loaded, we

actually kept them relatively simple. We put in crowds and

things if it really helped the story, but not as a general rule.

We would try interesting angles, we didn't just load it up for

the sake of loading it up. I think that's why a lot of those old

Dell comics look so good. They were thought through from a story

standpoint.

I never treated a comic book script the same as I would an

animation script when I board them. They're just not the same.

They're two different media. There was an interesting

experiment. I can't recall the company that did it, but they

tried to blow up comic book panels, and thought they would save a

lot of drawing and work, just blowing them up. It just never

worked. No matter what they did, it just didn't blow up

properly. In other words, they're just two separate media,

really.

Q: What project or film or show or something that you've worked

on, has given you the most professional enjoyment or satisfaction

and why?

PA: I would say my experience at Warner Brothers was kind of

special because of all the talented guys, even when we didn't

agree on everything. In fact, we did a lot of disagreeing. All

of us were really concerned with what was on the screen, and we

were all very professional. They did give us a certain kind of

freedom. We had a certain schedule to adhere to, but we could

adjust that to fit our own way of working. If you had a five

week schedule, that's about what we had roughly to do lay-outs or

background. And actually, we could do it much faster most of the

time. We'd use that extra time to put little things into the

film or maybe save it for another film we wanted to put a few

more hours of thinking on or try to improve it. But it was a

good time for me because it was one of the rare times when I

always looked forward to going to work (laughs). I guess it

wasn't all that perfect, but time's probably mellowed me

(laughs).

Q: A project, on the opposite side, that failed, in your opinion.

It may have been a commercial success, but you personally felt

did not live up to your expectations.

PA: Well, I was going to say ROCK ODYSSEY. I had a lot of hope

for that. I think we did a lot of nice work on that thing, but

it just never seemed to get off the ground. I think most of us in

the business are so close to these things, we don't really know

sometimes when we have something.

Q: And the final question now: if you were to start in the

business today, or to offer advice to someone starting in the

business today, what would you tell them?

PA: Well, by all means, I would say get as much art schooling as

you can, or expose yourself to as many good teachers, whether

they're animation people or otherwise. First of all, get

yourself a broad, well-rounded knowledge of art, generally, then

specialize, if you want, in animation.

Get the fundamentals under your belt. If you're self-taught, go

to the library and get lots of books. You can't lose by keeping

a lot of books for reference. They're always great to lift your

spirits and keep your level of quality up.

Back To Contents

Back To Main Page