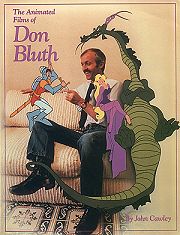

The Animated Films of Don Bluth

The Animated Films of Don Bluthby John Cawley

The Disney Years

The Animated Films of Don Bluth

The Animated Films of Don Bluthby John Cawley The Disney Years |

|

Don Bluth began his Disney career during the Fifties, but it was a brief experience. "I found it kind of boring," stated Don. However after spending time traveling the world, finishing school and doing live theater, Don decided that animation was in his blood. After a three year stint at Filmation, he joined the animation staff at Walt Disney Productions in 1971. This was a new Disney for Don. Walt was dead and the studio was headed up by a committee that included Ron Miller, Walt's son-in-law. Don recalled that period in a 1989 interview. "At Disney, everybody was trying to do what they thought Walt would do. Every time you opened a cupboard, there was his picture. 'What would Walt do?' I think you need living leaders working in the current environment. Walt was gone and trying to guess for a dead man wasn't productive." In charge of the features was Woolie Reitherman, one of Disney's most talented animators. Reitherman was responsible for such key scenes as the dinosaur battle in FANTASIA and the moody final fight between Tramp and the rat in LADY AND THE TRAMP. The last film released by this new Disney was THE ARISTOCATS (1971). It seemed a far cry from such classics as BAMBI and CINDERELLA. Don and fellow newcomer Gary Goldman decided they would try to rebuild the studio. They were soon joined by John Pomeroy. At first they were merely three more animators to be trained by Disney's famed Nine Old Men. These classic animators, such as Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnson, had been animating on Disney features since SNOW WHITE. This triumvirate of talent wanted to make the new films look as good as the old films. Whenever they would approach management, they were told it would cost too much to do what they wanted. Soon, Don, Gary and John had set up a makeshift studio in Don's garage and went about trying to do things the old way. Don wrote, "We'd come into work at the studio each day and ask the veteran animators, the men who'd worked with Walt since the early days, how, for instance, they had made the water look so wet in FANTASIA. Mostly we discovered that the men had forgotten how they'd done it. No one had written down the process, so we had to start from scratch, but we figured out the process and found that they weren't too expensive at all." The trio found that most of the time and expense used in the classic films was no longer available to the newer talent. They began studying the art and records of the older films to discover how the original films were done. One area that they found most lacking was the use of special effects. Don's desire to return to a more classic look did not go overlooked. His knowledge of early Disney and his ability to talk about goals for animation made him highly visible to the animation crew. In short time, he obtained a following that slowly grew. Disney publicity noticed this new "animation guru" and began exploiting him. It was obvious to upper management and the publicity department that the Nine Old Men would not always be around. Since Walt's death, there had really been no focus on a personality at the studio. The Nine Old Men were a group who could discuss the way "Walt did it," but didn't seem to connect with a generally young audience. (It was an audience that hadn't quite caught the animation fever that would come in the early Eighties.) Don became one of Disney's newest publicized faces. According to many press releases of the time, he was one of the new talents being trained by the old pros. He was the driving force behind a new look at the studio. He was helping Disney animation move into a more classical mode. Along with help from numerous other artists, writers and directors, Don was seen as one of the reasons the films began moving away from the silly sitcom look of the early Seventies (with THE ARISTOCATS and ROBIN HOOD) into a more serious mode (THE RESCUERS and THE FOX AND THE HOUND). The Disney studio's publicity biography of Don from 1977 referred to him as "the head of the young team of animators especially trained to carry on the traditions and quality of animation established by Walt Disney and his original team." It goes on to state "He is the first of the new group to attain the rank of animator and serves as inspirational and motivational leader to the others as well." In 1976, the New York Times ran a major piece on the re-building of the Disney studio's animation department. The author talked with a variety of the people in charge, including Ron Miller and Woolie Reitherman. Both men had a number of kind statements about the new crew. The article even dubbed a new group of "nine young men." It failed to list all nine, but did give key focus to Don Bluth and close associate Gary Goldman. (John Pomeroy was pictured in the piece.) Others mentioned or quoted in the article included storyman Pete Young and animators Andy Gaskill, Dale Baer and Chuck Harvey and assistant Allan Huck. The article pointed up that Don had become the first of this new group to achieve the status of animator repeating the statement that "he is regarded as a kind of inspirational leader." Don found a forum for his belief in what an animated film should do. "Before you say anything, you must have something to say," he would tell newcomers, "and it can't be, 'My purpose is I want to make more money.'" Earlier that year, a re-issue of SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS had earned over $11 million at the box office, making it one of the higher grossing films of the year. Don used this as a weapon in his discussion. "SNOW WHITE's success last Christmas should be writing on the wall to the businessmen. I say that what those grosses mean is that there are a lot of people out there looking, not for the arena and the lions - the pictures like JAWS - but looking for beauty." Besides the desire to bring a classic look back to Disney, Don enforced his belief in creating a true animation team. He knew that animation took a large number of people all handling different jobs. In an interview from the time, Don stated, "My concern is that all the young guys team well. When the volleyball net was up near the commissary, we had all the trainees at least talking to each other once a day. Then the volleyball net came down to make way for the construction of a new administration building. There was no more daily communication. Cliques began developing. I went right to Ron Miller. I said, 'Ron, you're an athlete. You know about team spirit. Well, the new generation here needs to touch base with each other at least once a day. So we need a new volleyball net.' Ron said, 'Great,it shall be done.' Now they're putting one up in the North Berm." Even at Disney, Don wanted more control over the entire process. "Right now, we make storyboards, then we animate them, then we go over here and we color the animation, and then we add music later. It isn't put together as a whole: the animation caring about the background; the music and color - which you can't divorce, they go together - caring about the story and the story caring about what happens to the characters," advised Don in another Seventies interview. Don also discussed the types of projects Disney was handling. "We haven't been telling better stories than SNOW WHITE, and we should be. We're doing the same thing over and over again, but we're not doing it any better. Yet we know enough now so that we should be preparing the films in which the color and the music and the layouts and the backgrounds all change to fit the moods of a story in which everything combines to touch you. The pictures now are entertaining, they're fast-paced, and they're clear. Walt had all those things, and he touched you besides." In some ways it looked as if Don was to take over the creative spot at Disney. During the late Seventies, it was discussed that Don might take over Woolie Reitherman's position and become the main director. This is not to say that Don was without detractors at the studio. His fast rise and desire to revise the animation department did not meet with everyone's approval. Dave Spafford, one of those who left Disney with Don, recalled some of the atmosphere. "The studio was full of new talent, like myself. Don came along and he was one of the best of the new artists, and he had some excellent ideas. But some of the other newcomers would say, 'Well he didn't work on PINOCCHIO. He's not one of the old timers. Why should we listen to him.' When Don got the attention, they felt they should get it. It got to be quite political all of a sudden." Such squabbling was not on display for the press, who had

management and Don to talk to about the studio's operation and

budding new animators. Don had done his homework in animation

and it paid off. Oddly, it was the work at home that was to make

the name of Bluth a Disney competitor rather than Disney

compatriot.

|

|

Return to Table of Contents Return to Get Animated! Main Page text and format © John Cawley |